“ The space of one man's sensible objects is a three-dimensional space. It does not appear probable that two men ever both perceive at the same time any one sensible object; when they are said to see the same thing or hear the same noise, there will always be some difference, however slight, between the actual shapes seen or the actual sounds heard. ”

Bertrand Russell, Mysticism and Logic and Other Essays (1910). copy citation

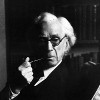

| Author | Bertrand Russell |

|---|---|

| Source | Mysticism and Logic and Other Essays |

| Topic | noise difference |

| Date | 1910 |

| Language | English |

| Reference | |

| Note | |

| Weblink | http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25447/25447-h/25447-h.htm |

Context

“The space of the real world is a space of six dimensions, and as soon as we realise this we see that there is plenty of room for all the particulars for which we want to find positions. In order to realise this we have only to return for a moment from the polished space of physics to the rough and untidy space of our immediate sensible experience. The space of one man's sensible objects is a three-dimensional space. It does not appear probable that two men ever both perceive at the same time any one sensible object; when they are said to see the same thing or hear the same noise, there will always be some difference, however slight, between the actual shapes seen or the actual sounds heard. If this is so, and if, as is generally assumed, position in space is purely relative, it follows that the space of one man's objects and the space of another man's objects have no place in common, that they are in fact different spaces, and not merely different parts of one space.”

source